“Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes.”

— Geoffrey Chaucer, ‘Canterbury Tales’ General Prologue

“Anglicanism is a mess—a beautiful mess, but still a mess.”

I do love being Anglican. If I hadn’t encountered God’s embrace in Anglicanism’s sacramental life and open sensibility, I’m not sure I would have returned to the Church at all. So, I am truly, unfeignedly thankful that our Communion exists. But I must confess to making apologetic statements like this on behalf of our tradition on a semi-regular basis. Friends from every ecumenical quarter are often puzzled by the amorphous phenomenon called ‘Anglicanism,’ variously poking fun at and valiantly struggling to understand who and what we are.

And honestly, I have often shared their puzzlement. With piety and preaching that runs the whole Protestant-Catholic gamut, it’s hard to pin down what exactly ‘Anglican theology’ is or even, as some question, whether it exists. The capaciousness and adaptability that make Anglicanism so baffling have been an undeniable boon to many—especially those seeking refuge from rigid and overly-specified dogmatic programs of some other Christian traditions. But I think we need to attend to the subtle boundary between capaciousness and confusion.

Just a cursory glance at the state of our Communion demonstrates what happens when we enshrine ambiguity to the extent that our sense of shared identity gradually erodes. As the current rifts over gender and sexuality showcase, we simply can’t agree on what Anglican doctrine, theology, or practice ‘really’ is. It seems clear that if Anglicans are going to exhibit the unity to which God calls the Church, we are going to need to find a new, shared vocabulary for describing our common theological identity.

All the Wrong Places

Some feel the understandable impulse to search for this theological identity in what we believe, delineating more clearly which doctrinal positions are permissible for Anglicans and which fall outside the pale of our tradition. After all, our canons and liturgies do claim some doctrines as essential—Jesus Christ is both fully God and fully human, for example. But there are immediately fatal errors in this approach to the search.

While basic doctrines are affirmed universally, the Anglican Communion’s capaciousness holds together wildly divergent, even contradictory, stances on any number of less essential doctrinal topics. Any crystalized formulary of ‘Anglican doctrine’ will either reflect a bygone era of greater apparent uniformity (e.g., the 39 Articles) or be so generic as to hardly describe Anglican theology as such (e.g., the ecumenical creeds). We Anglicans certainly do believe and teach many things. But we believe so many things—so many different things—that our doctrinal amalgam seems a shoddy foundation for shared identity.

But what if Anglican theological identity instead resides in how we decide what we believe? Can we turn to some Anglican theological method with a sense that even if we arrive at divergent answers to doctrinal questions, we share a common way of pursuing those answers? In daily parish life, this effort to establish Anglican identity manifests in the popular ‘three-legged stool’ (Scripture, Tradition, and Reason) so infamously misattributed to Richard Hooker. And even if we avoid such oversimplifications, there is an allure to defining Anglican theology as a carefully reasoned reading of Scripture through the lens of Tradition.

Step back for a moment, though. Surely Anglicans are not the only ones who would claim such a method as their own. In fact, I’d venture that few in the major Western Christian traditions would balk at subscribing to (and demonstrating!) such a theological methodology. Perhaps some would arrange the terms of the equation in a different order, conjoined by prepositions with subtly different shades of meaning. But we share this fundamental approach with our Roman and Old Catholic and Protestant siblings. Anglicans may have made it more central to our ‘branding,’ but this method is hardly distinctive of our theology at any substantive level.

Some argue then that Anglicanism is characterized not by how we do theology (methodology) but who we say we are (ecclesiology). Anglicans’ particular constellation of ecclesiological commitments (the historic episcopate, conciliarism/synodality, etc.) at least seem like a locus of unity. But while those ecclesiological commitments are certainly distinctive, I question whether we can really anchor Anglican theological identity in these commitments.

The most fundamental problem with this approach is that our ecclesiological platform has not remained entirely consistent over time. For example, while we never abandoned historic apostolic succession, it hasn’t always been the sine qua non of full ecclesial communion that it is for us today. That development/clarification evolved over the 19th and 20th centuries, and many earlier Anglicans would not have insisted on it as strongly as we do now. So, I am inclined to say that while Anglican ecclesiology is distinctive, even that distinctiveness isn’t the root of our theological identity, but rather symptomatic of a deeper root.

Deeper Disposition

My own understanding of Anglican identity has emerged from an inductive study of a wide range of Anglican texts, searching for themes that point to a fresh conception of Anglican theological identity. On the one hand, sifting through this material did affirm that our tradition is relatively lacking in coherence at a surface level. But still, as I looked beneath the surface of doctrinal positions and even method, I did notice a pattern that persists across time and partisan rift. This pattern is a shared ethos among Anglican theologians: an implicit vision of what the Church is about and for.

One might reasonably object that this sounds like ecclesiology. It is, in the sense that I see Anglican theological identity as rooted in our vision of the Church. But there are a couple reasons why I think the pattern I’ve observed differs from our constellation of ecclesiological commitments discussed above. For one thing, this pattern is implicit. A few 20th century writers on ecclesiology (principally Michael Ramsey and Daniel Hardy) do start to grasp at what I’ve observed. But otherwise, I did not see this underlying vision of the Church expressed explicitly in the body of Anglican theology since the Reformation. In order to discern this root of our theological identity, I think we have to look deeper, beneath the surface of the theology published by Anglicans.

Secondly, this implicit vision is, to a certain extent, ineffable. The pattern I’ve noticed is not a set of doctrinal propositions about the Church or an ecclesiastical policy platform from which the Anglican Communion reasons its decisions. What I see is a more fundamental orientation or posture that colors all Anglican theology and practice. The root of Anglican theological identity as I see it is subconscious—an assumed sense of what the Church is for, prior to any concrete claims about how the Church operates. This posture can’t be distilled into a pithy confessional axiom. It is a particular shape of the mystery of the Church within which all our theological reflection occurs. And as with all theological mysteries, we can only really articulate the disposition at the root of Anglican theology through metaphor, image, and model.

Model of Pilgrimage

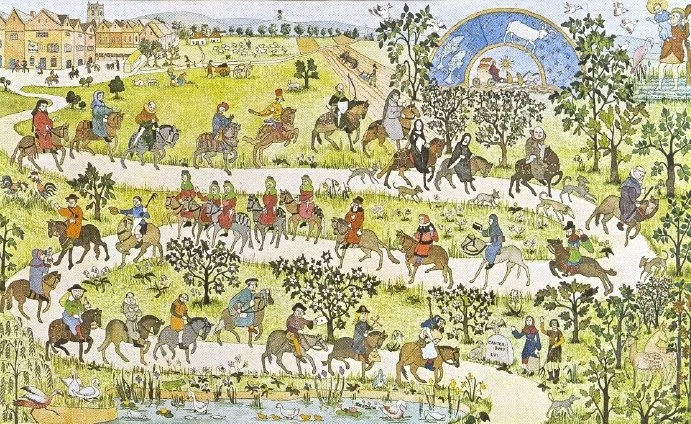

There are, I’m sure, any number of images that could be express the fundamental disposition I observe at the heart of the Anglican theological tradition. But as I worked through the various texts I’d assembled, the image that coalesced in my mind was that of pilgrimage. I would posit that the disparate strands of Anglican theology can not only coexist but even find actual unity in a shared sense of the Church as a journey of pilgrimage.

Propelled by an initial generative encounter with the Risen Christ, the Church sets out on a pilgrimage towards the culmination of that encounter in the eschaton. Experienced and renewed in the visible life of the Body of Christ, this encounter anchors and energizes the Church in its journey towards its heavenly destination. But along with confidence in continuing the quest, the Church’s enduring encounter with God also engenders a sense of our finitude, incompleteness, and even brokenness. The pilgrimage is a journey of continual growth, in and as the Body of Christ, into the fullness of what that Body is destined to be.

Demonstrating this disposition of pilgrimage exhaustively is the task of a future essay with more footnotes. But for now I’d like to offer five ‘notes’ of pilgrimage as I see them reflected in the Anglican tradition—in our questions, our answers, and our life together:

Commission

Every pilgrimage has a starting point, a place and time where it all begins. For the Church, that point is the encounter with God’s self-revelation in the life, death, and resurrection of his Incarnate Son. Anglicanism’s sense of purpose flows entirely from the Apostles’ encounter with Jesus that constituted and commissioned the Church. That’s why we are so doggedly insistent on Trinity and Incarnation as the essential dogmas defining the faith. We emphasize Scripture and the Creeds so strongly as rules of faith because they preserve the witness to that encounter that sets the Church on its path. The shape of this encounter—of the paschal mystery—is imprinted on Anglicans’ vision of the Church as a pilgrim people constituted and commissioned by God.

Visibility

Pilgrimage is the concrete endeavor of a concrete body—usually a visible community. This aptly captures the nearly singular emphasis of Anglicanism on the life of the visible Church. Anglican theologians throughout the years have spent very little time prognosticating about the ‘Invisible Church.’ Instead, attention is focused on the Church as we participate in it now. Our tradition emphasizes the Church today as a society visibly continuous (through faith, order, and practice) with the Church of the past, preceding and supporting the individuals’ faith. And I think this concern for the visible life of our pilgrimage shapes our particular interest in the Church’s unity and the active role it plays in the world. The Body of Christ is utterly concrete and active—mystical, but not ethereal.

Finitude

Pilgrims on the road are still incomplete, still yearning for their goal. Anglicanism embraces this sense of incompleteness and provisionality in the face of God’s Mystery, letting it temper our theological debates. Anglican theologians tend to be reverent in speech and reticent to make definitive pronouncements about the mind of God. Language is limited and humans can err—not merely individuals, but also the Church. The image of the Church as a heavenly reality is superposed with its human reality, marked by sin and capable of error. Yet for Anglicans, this finitude is not a cause for despair. The winding messiness of the pilgrim path cannot destroy God’s intention. He set the Church on its path and continues to be tangibly present with us; we just haven’t reached the destination.

Journey

Awareness of the destination still to come turns pilgrims’ gaze to the path right before them. For Anglicans, the sense of an incomplete mission turns our attention to the journey itself. This manifests chiefly in Anglican theology’s affinity for ‘practical divinity’ or theological reflection on the ‘nuts and bolts’ of Christian life. If the Church is a pilgrimage towards completeness in God, then all our theology should tend to the needs of that journey. Anglican theology is thus mostly occasional or topical, responding to the various particular contexts in which Anglican Christians are living. Ultimately, Anglican theology on any topic tends to return eventually to emphasize the life we live on this journey towards the end God intends.

Horizon

Just as a pilgrim’s whole being is oriented towards the shrine they will visit, Anglicanism’s entire posture points towards the eschatological fulfillment of the encounter with Jesus that started the journey. The destination is perfect unity in and with God. Every foretaste of Resurrection the Body of Christ experiences along the way—in Word and Sacrament and World—points towards the fullness of the New Creation, where we all will be one as the Son and the Father are one. Anglicanism has never much cared to speculate about what this end will be like. It simply holds to the promise, pledged in Christ at the outset and completed in him at the end.

These five notes are an attempt to sketch out the pilgrimage I see unifying the numerous streams of Anglican theology. But again, they should not be understood as a platform or as a ‘recipe’ for doing Anglican theology. In the end, this model of pilgrimage may not even be the best way to describe the disposition I see. But the reality the model grasps at is there. Holding fast to the anchors of the Church’s encounter with Christ and our destination of fulfillment in him, Anglican theology is grounded in our common journey towards the horizon.

The Maturity of Anglicanism

I maintain that, if you look beneath the surface across the Anglican tradition, you will see this deeper disposition—this constant, implicit sense that the Church is on a pilgrimage from an encounter with Christ towards the end fulfillment of that encounter. But this sense is just that—implicit. Only two major theologians I encountered come close to articulating this pattern explicitly. And while I have anecdotally seen pilgrimage-adjacent language filter into popular Anglican discourse (at least in America), other frameworks dominate the search for Anglican theological identity. This pilgrimage is an enduring feature of our tradition, but it has yet to become a clear part of our collective consciousness.

Articulating this disposition would, I believe, benefit the Anglican Communion greatly. We have been trying (and failing) to find unity by vying to make one or another theological criterion or platform the definitive shibboleth of Anglican identity. What if instead of drawing the boundaries of our identity we gathered around something that resonates across our varied perspectives. In a climate of ultimatum and schism, building such a centered identity might seem impossible. But I’d propose that what I have laid out here could be the nucleus of just such an identity for Anglicanism. It is already at the heart of who we are. The model of pilgrimage is my attempt to draw together threads I see already running throughout our tradition. Perhaps this pilgrimage disposition could be the basis for a centered identity that is discovered more than constructed.

In many ways I think making this underlying disposition explicit would be a journey of maturation for Anglicanism. For so much of our history we have had to define and justify ourselves in the midst of polemic. Sometimes we have brought this on ourselves; other times it has happened through no fault of our own. But while we are certainly capable of polemic, that is not who we are or who we are meant to be. If we are going to proclaim the Gospel in the world with any coherence or ‘integrity,’ perhaps a look inward is called for. Perhaps that will reveal what already binds us together: our shared pilgrimage along winding paths in the world towards the fullness of what we’ve encountered in Christ.