It’s so good to be back with you all. I’ve spent the last week in New York City for the first session of a 2-year leadership development program run by Trinity Church on Wall Street. If you’re not familiar with it, Trinity is one of the wealthiest parishes in the Anglican Communion. It has a truly mind-boggling endowment and budget. And its office building in downtown Manhattan feels far more like a massive corporate headquarters than the small parish offices I’m used to. By all financial or numerical metrics, it’s a highly ‘successful’ church. So while I was definitely excited about this opportunity, I have to admit I was also apprehensive that I was stepping into a world that would be all about ‘success’—successful leadership, successful ministries, successful churches. But I ended up being reminded of something quite different.

We live in a very success-obsessed culture. The way we structure our jobs, the way we assess our relationships, the way we build our budgets—the world trains each of us to strive for ‘success’ of some kind. And if you think you’re exempt, I’d invite you to consider the many different forms success can take in our minds. For some, success is excellence and being held in high regard. It’s about the superlatives: being the oldest, the first, the biggest, the best. For others it’s more ordinary: fitting in with the world around us belonging & being recognized as part of the group. Then of course, there’s the dominant one in America: success as financial prosperity or security. The classic ‘American Dream’ is a dream of success. It might not necessarily mean an extravagant lifestyle, but for most of us, success involves at least having enough to live comfortably.

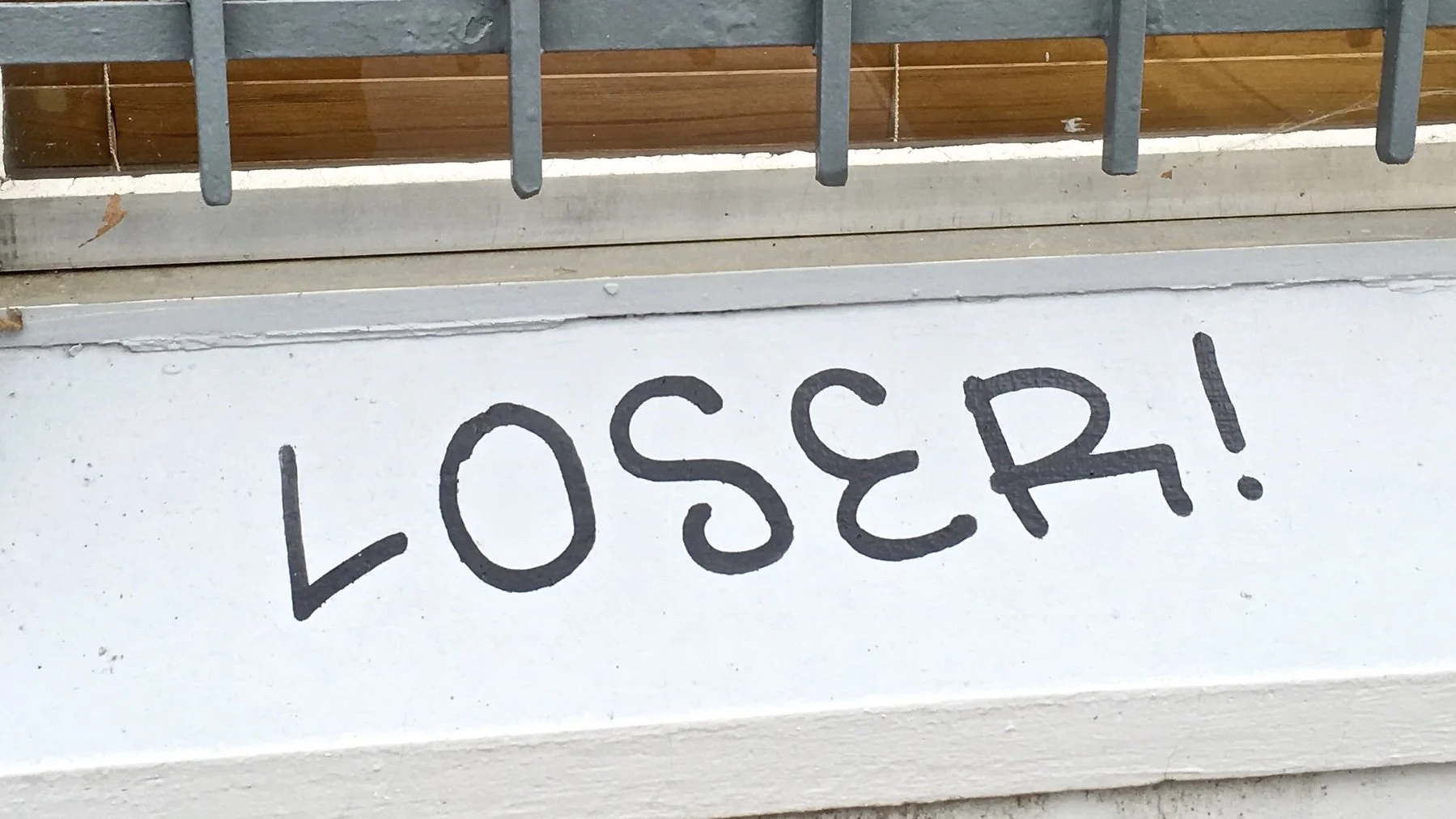

The form of success you find yourself pursuing might change from day to day or over the course of your life. But regardless of which metric we gravitate towards, I’d wager that all of us yearn for success in some way. It’s a yearning that’s baked into the culture which subtly shapes you and me as we go about our days. And this preoccupation can manifest in obvious ways, like in public displays of derision towards ‘losers.’ But our pursuit of success is equally present in more well-intentioned dreams—like dreams of an ideal, ‘successful’ church. The single-minded pursuit of success is not uniquely the path of megalomaniacs. It’s a path that the world beckons most, if not all, of us to follow.

But as our readings today make quite clear, the path of discipleship that God calls us to follow, looks very, very different from the path of success. In our gospel, Jesus holds up the example of a child—utterly without power or rights in their society—and urges the disciples to set their hearts on being last and least and servant of all. In the reading from Wisdom, Solomon issues a creative invitation to live in a way that is profoundly countercultural. We see that righteousness is a kind of lifestyle that makes us strange and inconvenient and even despicable to the world. And then in his critique of conflict caused by cravings and greed, James reminds his flock that the gifts God offers are not for ourselves—to be spent on our own pleasures. He reminds us that, as our own bishop says, “The economics of the Gospel is that we are fed by giving ourselves away.”

This is the path of discipleship—the Way of Jesus that we claim to follow. And it seems like a pretty raw deal. It’s certainly a far cry from the pursuit of worldly success, however we might measure it. But a lot depends on our perspective—on the spiritual lens through which we view our lives. Remember Jesus’ rebuke to Peter last week. When the apostle protests against the idea of Christ’s Passion, Jesus says, “Get behind me, Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.” It’s a distinction echoed in our opening collect today: “Grant us, Lord, not to be anxious about earthly things, but to love things heavenly.”

There are two vantage points—two points of view as we consider the paths of our lives: a perspective focused on heavenly things which shall endure, and a perspective focused on earthly things which are passing away. If we see only the things that are passing away, then of course we will shy away from the path of discipleship. If our life is merely “short and sorrowful” as the ungodly characters say in the book of Wisdom, then who would want the fate of the righteous man, who renounces his claim to every metric of success and as a result is insulted and tortured and put to a shameful death?

But if we admit that there may be more to life than earthly things that pass away—if we admit that Jesus’ path might lead to something of more eternal significance then we will start to see how the path of worldly success is actually quite hollow. Pursuit of superlative excellence and others’ high regard traps us in a kind of self-centered obsession, endlessly comparing ourselves to where others are or where we could be. Successfully fitting into a world that has rejected ultimate meaning consigns us to what Solomon so provocatively calls ‘the company of death’. We find belonging, yes, but by belonging to a nihilistic covenant that lets death have the last word. And chasing after prosperity and economic security fixes our gaze on what we lack or might lose, sowing the seeds of envy and anxiety in our hearts.

The path of ‘success’ might seem like making the best of this life. But it also sets that life up to be pretty “nasty, brutish, and short.” If we fix our minds on earthly things—reputation, belonging, prosperity—in pursuit of success, we are liable to lose sight of the bigger picture: the Kingdom of Heaven—the New Creation inaugurated in Christ. If, however, we learn to love heavenly things instead—if we train our hearts to love what God loves and focus on the abundant life that God intends for the world, then we will see how the path of discipleship does ultimately lead to an eternal reward.

Weakness and lowliness does, in fact, lead to greatness. When we are least of all and servant of all, God makes us great in the Kingdom of Heaven. When we let go of the need to succeed by excelling, then we truly excel in ‘gentleness born of wisdom.’ The life centered on growing in God does, in fact, lead to belonging. When we embrace our identity as children of God, we find ourselves nestled in the embrace of Christ. When we stop chasing the success of fitting in with the world, then we truly belong to the company of new life in Christ. And the economics of the Gospel—making it a priority to give ourselves away—does, in fact, lead to prosperity. When we accept that all we have is a gift freely given, envy and anxiety about economic security starts to fade. When we give up the pursuit of financial success, then we can truly give freely from the wages of holiness.

This Christian life that our readings lay out is not a recipe for ‘success’ in the world. But as Mother Teresa put it, “God has not called [us] to be successful. He has called [us] to be faithful.” And being faithful will probably mean that we look like losers. We may well be small and insignificant in the sight of the world. The priority we place on being members of Christ may well seem weird or even ridiculous to our friends. And the freedom with which we offer our time, talent, and treasure may well involve discomfort at times.

If this short and sorrowful life were all that there is, then it would be foolish to set down success and follow Jesus like this. But if we believe, even a little, that life is more than worldly ‘success,’—that God wants more for us than making it big, or fitting in, or living the American Dream—then we owe it to ourselves to take up our cross and follow Jesus on the Way of Love. Because it is in learning to let go of ‘success’ in the world, that we are freed from from anxiety about things that are passing away. It is in learning to be faithful losers like Christ, that we receive a deeper confidence in an eternal reward—an abundance which shall endure which shall feed us no matter how much we give it away.